Communist Vietnamese art of an attack. Artwork: The Year of the Tigers (3rd edn).

The Battle of Binh Ba Revisited from the histories of both sides.

By David Wilkins, OAM

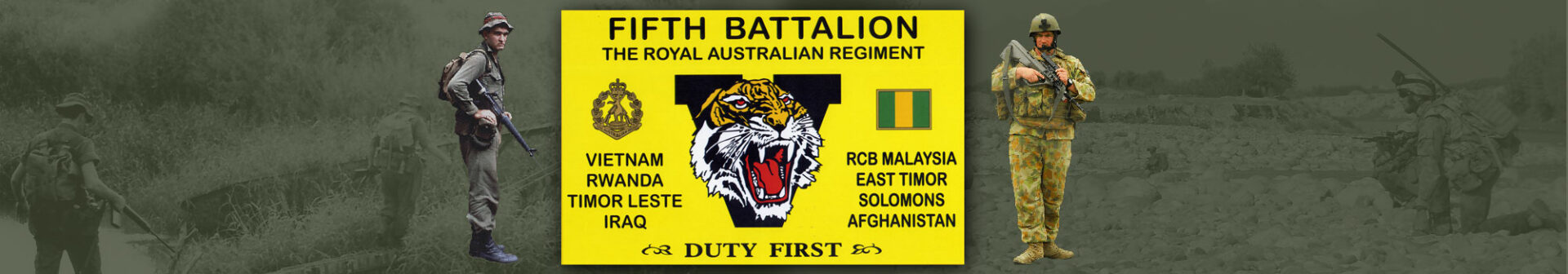

Former Adjutant, 5RAR, 1968-69

The fiercest urban battle fought by the Australians in the Vietnam War occurred in June 1969 at the village of Binh Ba. As time passes, more information is revealed about what the enemy planned and what actually happened during that encounter. Very much instrumental in revealing this to Australians has been Ernest Chamberlain, a former member of the Australian Army Intelligence Corps and Vietnamese linguist.

Chamberlain served as an Intelligence Officer in Vietnam in 1969-70 and later worked as the Vietnam desk officer at the Joint Intelligence Organisation. He was Director of Military Intelligence and then became Australia’s Defence Attaché in Cambodia and Indonesia before retiring as a Brigadier. Chamberlain has researched Communist Vietnamese military documents and histories and interviewed a number of their former unit veterans and dignitaries including, as are relevant to this article, from 33rd North Vietnamese Army (NVA) Infantry Regiment, D440 (Long Khanh’s Own) Battalion and C41 Chau Duc Company. His translation and critical analysis of these Vietnamese unit histories have been invaluable to the Australian military history of the Vietnam War and I am grateful for his permission to quote extracts. They reveal information of enemy planning not previously known to Australian historians.

Background and enemy planning

On 20 May 1969 a meeting was scheduled for 8 June at Midway Island between US President Nixon and South Vietnamese President Thieu. When this meeting was (unwisely) publicly announced in advance, the Communist leadership planned their own public relations response which would also coincide with the formation of its own Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG) on 10 June. That response was a period of ‘High Point’ attacks across South Vietnam for the first half of June, to emphasize their ‘continuing capability to conduct offensive action throughout South Vietnam.’

Part of this ‘High Point’ strategy included 122 enemy-initiated attacks in III Corps. Within Phuoc Tuy Province a major attack was planned on the ‘strategic’ village of Binh Ba with subsidiary attacks on Hoa Long and Hoi My villages.

Binh Ba (population of about 1,300) was a village adjacent to the French-owned Gallia rubber plantation, located on Route 2 just 6½ kms north of the 1st Australian Task Force (ATF) base at Nui Dat, while Hoa Long was 3 kms south of Nui Dat. Hoi My was further away to the south of Dat Do town.

Central to this Communist plan was the ‘The Heroic 33rd Infantry Regiment’, which according to its own history (translated and analysed by Chamberlain), had been raised in North Vietnam in 1965 and deployed into South Vietnam via the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Laos and Cambodia. On this occasion it was tasked by its superior HQ for Military Region 7 (MR 7) to coordinate with D445 (sic D440) Battalion and local force troops to launch a campaign on Route 2 from north of Binh Ba to the Song Cau creek line just north of 1ATF base. In fact, it was D440 not D445 that fought at Binh Ba. A special task allotted to 33rd Regiment in this plan was to ‘attack an Australian mechanised battalion [sic] … stationed in the Nui Dat area.’

The D440 Battalion history of 2011 records that, in late May 1969, it was operating in the Xuyen Moc area (see Map 2) when it received orders to ‘move swiftly’ to occupy Binh Ba village and ‘to prepare for the battle to be launched in coordination with the 33rd Regiment’. The plan was for D440 Battalion to capture parts of Binh Ba village including 664 (sic 655) Regional Force (RF) Rifle Company post, 1 the police post and the defensive positions of the Peoples Self Defence Force (PSDF). It was chosen for this task because its troops ‘knew the terrain and, moreover, the tactic of “attacking a post and destroying the relief forces” was the forté attack method of the Battalion that had frequently been quite productive ever since joining the battlefield.’ Its A Company was to then remain within Binh Ba to lure rescuing forces, including Australians from Nui Dat, so they could be ambushed by 33rd Regiment in the area between the bridge over the Song Cau and Duc My (500 metres south of Binh Ba). They were here describing their tactic of ‘luring the tiger from the mountain’ to then ambush it. The remainder of D440 were to remain adjacent to Binh Ba and conduct further attacks as the battle progressed. The enemy plan also included Chau Duc district troops and local guerrillas coordinating an attack on the Ap Bac hamlet of Hoa Long village (see Map 4). As Chamberlain has recorded, information on the planned NVA ambush was only revealed in 2012 through the Communist unit histories and had not been included in earlier Australian publications.

But the enemy plan was partly hijacked by Australian troops near the abandoned village of Thua Tich when, on 29 May, D440’s reconnaissance party was ambushed on Route 328 by 2 Troop, B Squadron, 3rd Cavalry Regiment (APCs) (under Captain Tom Arrowsmith) with attachments from 1 ATF’s Defence & Employment (D&E) Platoon and a section of 5RAR’s Mortar Platoon. Of the 11 enemy killed in action (KIA) and three wounded in action (WIA), one was D440’s Second in Command, ‘Comrade’ Ba Kim. As the D440 history relates, ‘even before a shot had been fired, the Battalion was in an adverse situation’, but notwithstanding that, the main body of D440 was still able to deploy towards Binh Ba and on 3 June, cross Route 2.

Then on 4 June, D440 was further surprised by ‘an Australian commando company’ that swept into D440’s camp west of Route 2. This was by the Anzac Battalion, 6RAR/NZ, during Operation (Op) Lavarack. (‘Commando’ is a term used in several Vietnamese communist military histories to describe Australian infantry troops in their small-scale operations, as well as Special Air Service (SAS) troops, who were also referred to as phantoms/ghosts of the jungle).

Consequently, because of this sudden, unexpected Australian attack on D440, a 33rd Regimental history noted, ‘the Campaign Headquarters adjusted the plans for the force to attack Binh Ba. This now involved an element of the 1st Battalion of 33rd Regiment, led by Battalion commander, Comrade Trieu Kim Son, being given the task of attacking the Binh Ba post, replacing D440 Battalion….’ which was tasked with ‘…fighting the enemy at the reinforcement blocking position on Route 2, together with the 2nd Battalion of 33rd Regiment…ready to strike …any enemy relief force…’ 2

According to 33rd’s ‘Their History’, on 5 June 1969 at dawn, D440 Battalion changed places with 1st Battalion 33rd Regiment to block any enemy relief forces along Route 2 to Binh Ba. Ambushes were planned for both north and south of the village.

Australian Task Force dispositions

In June 1969, 1ATF, commanded by Brigadier C.M.I. (‘Sandy’) Pearson, was operating from its Nui Dat base in Phuoc Tuy Province, part of III Corps, South Vietnam. 6RAR/NZ was deployed north of Binh Ba on Op Lavarack in Area of Operations (AO) Vincent and was experiencing increasing numbers of contacts with enemy forces. In the early hours of 5 June, 6RAR/NZ clashed with elements of 33rd NVA Regiment Rear Services near Phuoc Tuy’s northern border with Long Khanh Province. Later that day 3 Platoon, W Company of the 6th Battalion was almost surrounded by aggressive enemy, later ascertained to be from D440 Battalion. 3 Although a VC main force unit, D440 mainly consisted of NVA soldiers, having been raised in the north in 1965 before infiltrating to the south.

On 6 June, 5RAR was either resting, training, employed on company operations, convoy protection or on ready reaction standby at Nui Dat, having recently completed six weeks of continuous operations (Op Surfside, Ops Twickenham I & II and Op Roadside) in Phuoc Tuy, Bien Hoa and Long Khanh Provinces.

Part of the 1ATF intelligence resources was the secret tactical intelligence unit, 547 Signal Troop, with a communications intercept and interpretation role.4 By monitoring the NVA and VC radio communications, this Signal Intelligence (SIGINT) Troop was able to track their movement. An important aspect of their work was the Aerial Radio Direction Finding (ARDF) equipment crammed into a Cessna aircraft from 161 Reconnaissance Flight with a 547 Signal Troop operator flying high over enemy deployments as our spy in the sky. 33rd NVA Regiment principally sent messages by Morse code on High Frequency (HF) radios, encrypted in complex codes with impeccable security and while the messages were mostly not interpreted or decoded,5 the location of their transmitters could be fixed and so their movement tracked. When higher Communist HQ, the Central Office for South Viet Nam (COSVN), was unable to deliver coding materials, the NVA/VC units were obliged to employ lower-grade ciphers for extended periods. This was of course, ‘manna from heaven’ for the SIGINT unit at Nui Dat. Aware of the Allied intercept operations however, the Communist forces reverted where possible to the use of couriers rather than radio communications.

It was this SIGINT direction-finding method that traced the movement of HQ 33rd NVA Regiment for the period 29 April to 2 July 1969, as shown on Map 1. This Defence Signals Directorate data was only released by the Australian Department of Defence in 2011 and reveals the end-of-week locations but unfortunately not the daily ‘fixes’. Accordingly, the straight lines joining the end-of-week locations do not accurately portray the actual routes taken. Map 1 does show however, that HQ 33rd Regiment moved from a base near the Nui May Tao Mountains to positions south-east then south west of Xuan Loc town (in Long Khanh Province) before returning to north of Nui May Tao in late May. From there the regiment deployed south-west into Phuoc Tuy Province as shown by the red dotted line on the map, crossing the substantial Song Rai River on the way. By 4 June they were in grid square YS 4284 about 4 kms north-west of 6RAR/NZ’s Fire Support Patrol Base (FSPB) Virginia and about 10 kms north-west of Binh Ba. From there they would next be seen and identified two days later in Binh Ba itself during the battle. Other information corresponding to this was the 6RAR/NZ message, logged on 3 June, of an ARVN report of 33rd NVA Regiment near the Song Rai River close to the Phuoc Tuy northern border. This would have been about 5 kms south-east of the red dotted line, closer to the thick orange direction line in Map 2.

Map 1- HQ 33rd NVA Regiment locations period 29 April to 2 July 1969. The red dotted line indicates the regiment’s deployment through Phuoc Tuy, across Route 2, to a position about 10 kms north-west of Binh Ba. Map: Defence Signals Directorate and Ernest Chamberlain.

Map 2- Movements of 33rd NVA Regiment and D440 Battalion towards Binh Ba and of C41 Chau Duc Company towards Hoa Long in May-June 1969. Map: Ernest Chamberlain.

According to the Australian Official History (A. Ekins with I. McNeill, Fighting to the Finish, Allen & Unwin, 2012, p.237) in a section entitled: ‘The enemy mystery’, it states, ‘there seemed to be no rationale for their (the enemy) actions. Australian commanders and intelligence officers were baffled. During the initial occupation of Binh Ba, 33 NVA Regiment had apparently maintained radio silence, eluding task force signals intelligence.

Chamberlain contends this to be incorrect however, as revealed by his translation and analysis of enemy unit histories, and, from the recently-released records of the 547 Signal Troop intercept of 33rd NVA Regiment’s active communications throughout May and June as it approached Binh Ba.

Indeed, on 4 June, 547 Signal Troop claims it had been able to locate both HQ 33rd Regiment and its 1st Battalion at different locations north-west of Duc Trung, a pro-VC hamlet, immediately north of Binh Ba (see Map 2). It was unable to track the 2nd and 3rd Battalions however, because, although those units were receiving traffic, they were cleverly not sending any revealing messages.

In their book, The Story of 547 Signal Troop in South Vietnam 1966 to 1972 (2nd edition, 2016) R. Hartley and B. Hampstead state at page 375, ‘More than a week before [the Battle of Binh Ba], the [547 Signal] Troop had briefed Brigadier Pearson along with Intelligence and Operations Staff that ARDF fixes had indicated the movement of 33 Regiment into Phuoc Tuy Province from the north-east towards the general area of Nui Dat’.

As the expression ‘general area of Nui Dat’ is imprecise and seems not to coincide with their location fix in Map 1, of about 10 kms north-west of Binh Ba and at least 16 kms from Nui Dat, the accuracy of the statement appears to be questionable. Again, at page 378, ‘Due to the early warning time provided by the Troop, the Commander 1ATF had several days to prepare and deploy his Ready Reaction Force to any location that the 33rd Regt might attack’.

NVA signals operator. Photograph: The Year of the Tigers (3rd edn).

Australian 547 Signal Troop radio set room. Photograph: 7th Signal Regiment archives.

Post-war, Brigadier Pearson, wrote to the Australian military historian, Ian McNeill, ‘... we continued to track the NVA force which, in the main, slipped past 6RAR the following night.’ Whether or not the subject of 33rd NVA Regiment should have been briefed to the senior officers of the Ready Reaction force, Lieutenant Colonel Colin Khan, Major Murray Blake of 5RAR and Captain Ray De Vere of 3 Cavalry Regiment, is examined below under the heading ‘Discussion’.

33rd Regiment troops crossing the Sông Rai River in Phuoc Tuy Province, probably west of Nui May Tao. Photograph: Ernest Chamberlain.

The Battle of Binh Ba- the NVA and VC accounts.

According to a 33rd NVA Regimental history, at about 4pm on 5 June, the 33rd Regiment’s combat forces left their base (in the Hat Dịch area) 6 and were led through the jungle by liaison cadres to the battle area. This location is somewhat contradictory to other movement versions unless, as Chamberlain has explained, it was either an error or a reference to a position north west of Binh Ba after they had crossed Route 2. After four hours, their troops reached the assembly area close to their objective on the Binh Ba battlefield and awaited orders to attack. This assembly area was about 2,000 metres north-west of Binh Ba.7

On the night of 5/6 June 1st Battalion 33rd Regiment opened fire and attacked their objectives in Binh Ba village, where, surprised by the ferocity of the attack, Binh Ba defences quickly disintegrated. The NVA broadcast messages to the villagers to surrender and conducted a ‘proselytising’ (converting) mission by splitting up into cells to work with local VC in the people’s houses. According to the Chau Duc District History (2004), local village guerrillas were also involved in the operation and sustained some deaths in the later battle.

As related by a 33rd NVA Regimental history (Their History, of 2017) 8 the attack occurred as follows, with added unit identifiers in brackets. Note also that Bình Ba Làng was the main ‘residential’ village of Binh Ba while Bình Ba Xăng was the hamlet of Duc Trung to its immediate north with the rubber processing facilities.

The Regiment allocated a company from the 7th [1st] Battalion to attack and seize the Bình Ba strategic hamlet; two companies were sited to provide support and reinforcements for the company in the hamlets and to strike enemy relief elements. The 8th [2nd] Battalion – under Comrade Đinh Ngọc Thập, was sited in the north on Route 2; and the 9th [3rd] Battalion - led by Comrade Triệu Kim Sơn as the Battalion Commander was located to the south between the hamlets of Bình Ba Làng [Binh Ba village] and Bình Ba Xăng [Duc Trung] – ready to strike the enemy coming down from the Đức Thạnh SubSector and to coordinate with the 8th [2nd] Battalion in attacking any enemy relief force coming north from Suối Nghẹ9 and attempting to break through. On the night of 5 June 1969, the 1st and 2nd Companies attacked the hamlet of Bình Ba Xăng [Duc Trung]; and the 3rd Company of the 7th [1st] Battalion was tasked to attack the hamlet of Bình Ba Làng [Binh Ba village]. At first, the 7th [1st] Battalion assembled in an area of rice fields along the edge of the village to dig combat positions. At exactly H-hour, the Regiment opened fire on its objectives. Surprised by our determined attack, the enemy in the strategic hamlet in Bình Ba village were quickly routed – a number fled, and others huddled down to await a relief force. During that night, we took complete control of the battlefield and captured prisoners for questioning. The Headquarters raised the Liberation flag. Tân Phát (a section commander of the Bà Rịa-Long Khánh Armed Propaganda Group led by Comrade Huỳnh Thành Nhân) used four loud-hailers to call upon the enemy in the hamlet to put their guns down, surrender, and receive the leniency of the Revolution. However, a number of the remaining enemy in the post were stubborn and continued to resist. Nguyễn Văn Bảy – the Battalion second-in- command, ordered the companies to exploit the terrain and defend against enemy coming from the direction of Bà Rịa. The 1st Company was deployed in outer positions, and the 2nd Company was sited within the hamlet. The 3rd Company could not make contact – so, after the engagement, Comrade Mộc (the Company Political Officer) withdrew back to our base. At about 6 a.m. on 6 June 1969 – as anticipated, the Australian forces from Núi Đất sent their tanks to rescue the situation. Comrade Bảy ordered that the enemy had to be attacked and not allowed to advance. Nguyễn Văn Dụy – a soldier, and Nguyễn Văn Hoan – a section second-in-command in the main position, used a B40 to fire on and damage two M113s entering the hamlet. The enemy used their vehicles’ firepower to shoot into the people’s homes as they knew that the Regiment’s forces were sited in those houses. Then, the enemy’s helicopters attacked (at the time, we did not have our air-defence firepower with us). At 10 a.m., we reported that our anti-tank ammunition was spent. The enemy’s mechanised vehicles advanced in groups of two and three – and then grouped in a total of about 13 vehicles. The Australian infantry followed their tanks, but they fought in a guerrilla style – forming small groups moving around on the jungle’s edge. They were supported by aircraft and artillery in a massed attack, and we were completely surprised.

At this stage, neither the 8th [2nd] Battalion nor the 9th [3rd] Battalion were able to deploy, and the enemy in turn came from behind and moved to surround Bình Ba Làng hamlet [Binh Ba village]. From having the initiative, the soldiers of the 7th [1st] Battalion were then on the defensive – in circumstances where they had no pits or trenches in which to shelter. Communications had been lost, and – with the enemy’s fierce and heavy firepower, our casualties grew by the minute, and we had exhausted our anti-tank ammunition.

Faced with these difficulties, the Headquarters assigned our [either 33rd Regiment or D44010] RCL Platoon and an element of an infantry company from the D445 [sic D440] Battalion to break through from the direction of Bình Ba Xăng [Duc Trung]. However, that very direction had also been blocked by the fierce firing of the Australian tanks from the edge of the hamlet – wounding many of our men.11 With these indications that the enemy could wipe us out on the battlefield, we took the initiative to withdraw. The 2nd Company of the 7th [1st] Battalion in the hamlet reported to the Regiment that the 2nd Company had suffered casualties and – surrounded by the enemy, requested that a force break through to them. The Regiment radioed the 7th [1st] Battalion many times, but their actions were too late and lacked resolve. Consequently, 50 soldiers of the 7th [1st] Battalion were killed, including Comrade Nguyễn Văn Bảy – the Battalion second-incommand, and Comrade Bùi Quang Miền – the deputy political officer of the Battalion. Subsequently, the enemy used a bull-dozer to dig a deep pit in which they buried the bodies of 53 of those killed in a mass grave (three of the dead comrades were from the armed propaganda group). A number of our Bình Ba guerrilla guides were also captured such as comrades: Nguyễn Văn Bé, Lâm Văn Bạch, and Hoàng Văn Thành (Thái). Comrade Nguyễn Thị Xuân (Tư Thiên) – the secretary of the Party Chapter of the guerrilla unit headquarters, was also wounded in the face and taken to the Province hospital for treatment. These were great losses for the Regiment, and a battle from which we gained experience and many lessons.

The D440 Battalion history12 added that, Coordinating their infantry and tanks – and with artillery and air support, the Australians launched a decisive counter-attack on our elements holding-on in the village. From having the initiative, our forces were now on the defensive. Our forces were without shelters and trenches in which to take cover, and the very heavy enemy firepower resulted in increasingly heavy casualties. Almost all the soldiers in the company of the 33rd Regiment that was still holding-on became casualties.

With the difficult situation faced by our fraternal unit – and as ordered by the Campaign Headquarters, the Battalion Headquarters deployed a recoilless rifle platoon and part of an infantry company to break through the enemy blockade from the direction of Bình Ba Xang [Duc Trung] hamlet.13 However, this force was itself decisively attacked by Australian tanks right from the edge of the hamlet, and many of our troops were wounded. Our combat troops were brave and set fire to a M.118 [sic] tank, but were unable to break through the blocking position or defeat the enemy’s frenzied counter-attack. Next, in the face of indications that the enemy could sweep the battlefield clean, we took the initiative to withdraw. With a breaking of the enemy blockade unsuccessful, there was no time to collect weapons - and the enemy seized one of our two 75mm recoilless rifles, one of the Battalion’s principal fire support weapons.

The above 33rd NVA Regiment history contains several errors and inconsistencies, probably because it was reconstructed many years after the war had ended and, as the translator Chamberlain noted, the 33rd Regimental history writing team in Vung Tau was dominated by Baria-Vung Tau Province politico-military cadre without personal first-hand knowledge of the operations. As well, the ‘The Heroic 33rd Infantry Regiment’ certainly had a vast history to reconstruct, of constant combat from 1965 to 1975 in the ‘The American War’ followed by involvement in the South-West Border War against the Khmer Rouge and occupation of Cambodia in 1978, sustaining over 13 years, a total of over 4,000 cadre and soldiers killed or missing. One of the inconsistencies noticed is the location of 2nd Battalion 33rd Regiment in ambush- as mentioned above, it was sited south of Binh Ba in one version but north in another. Clearly their contemporaneous battle records were not nearly as accurate as in the Australian system. The differences in the versions of the battle are revealed in the Australian account.

The Battle of Binh Ba- The Australian account.

On the morning of 6 June, unaware of the attack on Binh Ba, a Centurion battle tank and an Armoured Recovery Vehicle (ARV) were travelling, unescorted, up Route 2 from Nui Dat towards Binh Ba, responding to a call for a replacement tank working with 6RAR/NZ north of Binh Ba on Op Lavarack. At 0720 hours the lead tank was struck by a Rocket Propelled Grenade 7 (RPG 7) fired from a Binh Ba house just 20 metres from the road. The turret was penetrated and damaged and a crewman wounded (Trooper Peter Chapman). Unable to use his main armament, he engaged the enemy with the tank’s .30 calibre machine gun (30 Cal MG). While the ARV, some distance behind, also engaged the target with its 30 Cal MG, the damaged tank pushed forward through the firing and reached Duc Trung where the wounded crewman was evacuated. The ARV pulled back and returned to Nui Dat. If the NVA thought this was the Australian reaction force, they were not only mistaken but also would have been surprised by the quick withdrawal of the two tanks.

Two South Vietnamese RF platoons were sent to investigate but were forced to withdraw under heavy fire. The District Chief, Major Ngo, then requested support from 1ATF. Although Binh Ba was within the Area of Operations of Lieutenant Colonel David Butler’s 6RAR/NZ battalion, the village itself was the responsibility of the District Chief should Butler’s unit be able to assist. But 6RAR/NZ was heavily engaged with other enemy contacts further north so Brigadier Pearson decided to alert his Ready Reaction force. D Company 5RAR, commanded by Major Murray Blake, was on 30 minutes notice to move as the Ready Reaction Rifle Company, together with a composite troop of three tanks from 1 and 2 Troops, B Squadron, 1 Armoured Regiment under 2nd Lieutenant Brian Sullivan, and 13 APCs from 3 Troop, B Squadron, 3 Cavalry Regiment commanded by Captain Ray De Vere. By 1000 hours the Ready Reaction force had departed Nui Dat, D Company severely understrength with just 65 men. Officers and NCOs were either on leave or on promotion courses so that just one platoon had an officer, 2nd Lieutenant John Russell (11 Platoon), the other two commanded by a Sergeant (Brian London, 10 Platoon) and a Corporal (John Kennedy, 12 Platoon). Many rifle sections were commanded by Private soldiers which Lieutenant Colonel Colin Khan later attributed to the depth of leadership existing in the companies at the time.

Initially the force was under operational control of Butler but at 1150 hours, with the additional deployment of B Company 5RAR, the command passed to Khan. 14 As the force advanced towards Binh Ba, the infantry mounted in the APCs, they had little idea of the enemy they would be opposing except for the report from a Liaison Officer at Duc Thanh of it being approximately two VC platoons.15 There had been no mention in their briefing of 33rd NVA Regiment being in the area. As the force passed the hamlet of Duc My, about 500 metres south of Binh Ba, they were engaged by automatic small arms fire but this was quickly silenced when the tanks returned fire with machine guns and cannister from their 20- pounder main armament. The force halted just out of RPG range at the south-eastern edge of Binh Ba and waited for clearance from the District Chief. They noticed civilians fleeing from the village.

At 1120 hours the District Chief was (wrongly) satisfied that all civilians had been cleared from harm’s way and gave his permission for the Australians to enter Binh Ba and ‘Do what you have to do’ and ‘knock down as many houses as you have to’. This indicated his belief that the only remaining people in Binh Ba were enemy. Blake, De Vere and Sullivan decided on an armoured assault, believing that dismounted infantry would be too vulnerable to enemy fire when in the open. De Vere, the senior armoured officer, took command during this phase of the operation but it reverted to Blake when the infantry later dismounted.

NVA troops attack. Artwork: The Year of the Tigers (3rd edn).

APCs and a tank arriving outside Binh Ba. Photograph: AWM film F04342.

The force formed up on the eastern side of Binh Ba and began advancing through the village, tanks leading, followed by the infantry-mounted APCs spread across the 300-metre width of the village (see Map 3). Soon after the assault began, 11 Platoon in the centre rear position, observed a number of civilians were still present and trying to make their way north out of the village. Russell requested permission to dismount so his soldiers could assist them to get clear. Blake consented, knowing this would reduce his flexibility but was mindful of the danger faced by the local population. At times while doing this, 11 Platoon had to fight their way through hostile positions. Blake still remembers quite vividly seeing ‘my men stop firing and run to move frightened civilians out of the way.’16

A Binh Ba family finding temporary shelter behind an APC during the battle. Photograph: AWM P10533.007.

D Company troops advancing into Bin Ba.

Tanks and APCs move through the village. Photographs: Photograph: AWM film F04342.

Enemy opposition intensified with automatic small arms (AK47), machine guns and heavier weapons including RPG 2 and 7 missiles. It soon became clear that within the village there was entrenched at least a main force enemy company. The show of enemy strength led Brigadier Pearson to dispatch a second rifle company from Nui Dat. It was Major Rein Harring’s B Company, 5RAR, which departed in APCs at 1150 hours and deployed into a blocking position to the south of Binh Ba. A South Vietnamese Regional Force platoon from Duc Thanh retained its blocking position to the north of Binh Ba. The battle tempo increased and became ‘fierce and confused’ as the Australians moved closer to the centre of the village. Hearing news of a Company size enemy group near the south west corner of the village, the two northern tanks surged forward to intercept them in the open. One tank was crippled by RPG fire but was still able to engage the south west corner before the crew was evacuated to the north by the other tank. Back at Route 2, the wounded (Corporal Geoff Bennett and Trooper Max Dale) were evacuated by ‘Dustoff’ helicopter. The fit tank was unable to return to the fray because of fierce enemy fire opposing it which left just two tanks fighting inside the village.

After fierce encounters and with the remaining tanks partially disabled from enemy fire together with crew casualties, the Australian assault force concentrated in a defensive position near the centre of the village where the two Centurions became the main focus of intense enemy RPG fire. It was this that led to the tank commanders, 2nd Lieutenant Brian Sullivan and Corporal Barry Bennier, plus crewmen Troopers Peter Matuschka and David Hay being wounded. The APCs also sustained a wounded crewman in this phase, Trooper Rod Beazley. The tanks and APCs poured a stream of devastating fire into the enemyoccupied houses but they were running low on ammunition. In fact, after 90 minutes of heavy fighting, the two tanks were in danger of being over-run by the nearby enemy. Major Blake estimated they were outnumbered by a battalion sized enemy and was concerned they too might be surrounded and enveloped by the larger force.

Two ‘Bushranger’ gunship helicopters were waiting for targets to be designated but were unable to engage any among the houses for fear of hitting the dismounted D Company infantrymen. Seeing this, Major Blake and Captain De Vere, ordered D Company to remount the APCs and, at a crucial stage in the battle, the ‘Bushrangers’ gave close support with their withering fire to relieve the emergency facing the Australians.

With ammunition low, it was decided to break out of the village to the south and on their second attempt succeeded in fighting their way free of the furious battle. It was now 1400 hours. Three of the four tanks had been damaged including the one that lay disabled and abandoned. The wounded were treated and evacuated and a fresh troop of three tanks (from 4 Troop, B Squadron) arrived. Major Blake ordered a second assault, this time from the west to east, but with infantry leading. At 1420 hours, the assault began, with D Company dismounted, supported by the fresh troop of tanks and their crews plus the APCs spread across the rear to the flanks. Blocking positions were occupied by RF/PF troops to the north and B Company 5RAR, relocated to the east.

The D Company platoons split up into house-clearing teams of 2-3 men with Sergeant Brian London, commanding No 10 Platoon of just 15 men, giving his orders: ‘The left and right clearing teams will move one row of houses forward and remain there. The centre clearing team, myself and the radio operator, will clear the single centre row. I will give the order to move forward and we will do it all over again. If you get into trouble remember we have a tank and two APCs at our rear, get word to me by runner if you need them, any questions?’ Heavy close-quarter fighting began immediately as they encountered fierce opposition. A member of 10 Platoon, Private Wayne Teeling was shot through the neck as his team approached the first line of houses. London recalled, ‘Corporal Bamblett and I reached Private Teeling but he was dead and all we could do was to drag his body out of the line of fire. Once this was done, I made contact with my tank and tried to speak to the commander using the phone at the rear of the vehicle but it wasn't working. Climbing up to the hatch I made contact and directed the vehicle commander to fire one round of H.E. [High Explosive] into the building.’ As the house exploded, the clearing team assaulted to discover six enemy dead among the ruins.

A pattern evolved as the small infantry teams cleared each house in turn. To dislodge the enemy, individual soldiers showed great courage as they exposed themselves to hostile action while either providing covering fire or running to a house. One of Blake’s strongest memories is of Private John Sturla standing in the open, his machine gun at the hip, covering two of his mates manoeuvring to throw grenades through a house window. Where the opposition was too strong however, they would call up a tank to use its main armament with a high explosive round to blast through the door or a hole in a wall, followed by a canister shell sweeping the inside with hundreds of steel projectiles. The infantrymen then went in, clearing the house room-by-room, throwing grenades or firing into the bunkers dug by the villagers for shelter but now being used by the NVA. Sometimes there was desperate, handto-hand fighting inside the shattered buildings reaching an intensity rarely equalled during any period of Australian involvement in the Vietnam War. Fighting increased again near the central village square adjacent to the schoolhouse emblazoned with the French word ‘École’. When, to the north, the infantry became pinned down by machine gun fire, a tank was deployed to assist but was forced back by intense RPG fire. An APC sped over open ground to outflank that enemy, killed the RPG team and neutralised the machine gun. Similar APC support was provided at different locations as the enemy clung on to fight tenaciously into the late afternoon. The abandoned tank was recaptured and heavy enemy casualties were inflicted. Despite some communications problems at times, the infantry-tank cooperation was ‘copybook’ with the infantry acting as the eyes and protection for the tanks in suppressing the RPG fire and the tanks reciprocating with heavy armament fire into houses where opposition was especially resilient. At times, civilians thought to have been evacuated earlier, emerged from houses and had to be ushered to safety. A platoon from B Company was at that stage sent to control and screen over 50 of them being moved to the north. Among them were two Viet Cong trying to pass themselves off as non-combatants and another, nursing a head wound. All three became prisoners. After four hours, by 1830 hours and with the battle effectively won, the assault force reached the eastern side of the village. Following this second phase assault, an exhausted D Company occupied a night defensive position to the south-east of Binh Ba while B Company HQ and its platoons adopted night ambush positions to the south of the village. RF/PF platoons remained in positions to the north of Binh Ba.

Binh Ba aerial from the south-east above Route 2 looking north-west. Photograph: The Year of the Tigers (3rd edn).

Map 3: Battle of Binh Ba (Day 1) schematic: • Phase 1- assault from east to centre and break out to the south; • Phase 2- assault from west to east. Map: The Year of the Tigers (3rd edn).

Despite the success of the combined armoured - infantry fighting, there existed the major problem of communications. Trooper David Hay, a tank radio operator in the battle, has noted the incompatibility of the American-made AN/PRC 25 radios carried by infantrymen with the British C42 and B47 radios fitted in the tanks, as the two types were unable to operate on the same frequency.17 Further, the infantry telephones fitted to the rear of each tank rarely worked as they had been constantly damaged during jungle operations. This meant that each tank could talk to each other but the APCs and infantry were unaware of the tank conversations and planned deployments. In addition to Private Wayne Teeling being KIA, D Company sustained two WIA: 2nd Lieutenant John Russell and Private Darryl Morrison. Meanwhile, at least 20 rockets and mortar bombs had been fired by the enemy at 1ATF base but without causing casualties. Fire Support Base Thrust also received 20 to 30 mortar bombs killing one Australian and wounding six from 9RAR.

Lieutenant Colonel Colin Khan, CO 5RAR, commander of the 1ATF Ready Reaction Force

D Company infantry supported by tanks and APCs clearing the houses in Binh Ba during phase 2 of the battle.

Lance Corporal Kevin Mooney of 11 Platoon.

Unidentified.

Major Murray Blake, (front) and WO2 Alex Smith, HQ D Company, 5RAR.

Infantrymen from D Company 5RAR in the process of clearing Binh Ba. Photographs: AWM film F04342.

Unidentified.

Private Jim Ward, of 11 Platoon.

Nguyễn Văn Dụy, 33rd Regiment, captured at Binh Ba and at a Regimental reunion at Phúc Thọ on 21 July 2013. Photographs: Left, AWM film F04342; Right, per Ernest Chamberlain.

The next morning, 7 June, there were three early incidents involving B Company and the armoured units, the first at 0320 hours, when two enemy were killed trying to escape from Binh Ba to the south, the second at 0600 hours involving an unknown sized enemy moving from the south and the third at 0645 hours when an estimated enemy company approached Binh Ba through the rubber plantation, also from the south and south west, only to be repelled by B Company, tanks and APCs on that flank.18 When the infantrymen swept the area, they found a body and blood trails indicating that six others had been wounded. They also captured the important 75mm RCL most likely from the D440 Battalion Recoilless Rifle Platoon, referred to above. Then at 0800 hours a section of APCs travelling south on Route 2 towards Duc Trung, the site of the Gallia rubber plantation’s processing factory, came under RPG fire and a group of 50 to 80 enemy was seen by an observation helicopter to be moving between houses. The Assault Pioneer Platoon from 5RAR was flown in from Nui Dat in readiness for action but Local RF troops were deployed into the hamlet instead. At 0950 hours, D Company with 5 Platoon from B Company, tanks, APCs and two combat engineer teams, swept through to the village centre from west to east conducting further house to house searches. It was nerve wracking work, not knowing if enemy would emerge and gruesome work retrieving the dead bodies. Three more wounded enemy were captured. By midday, they had cleared the western half of the village but they found the NVA to have withdrawn. The search was then handed over to PF troops who swept the eastern half of the village.

6 Platoon, B Company, 5RAR formed up prior to advancing with tanks and APCs upon Duc Trung. Photograph: The Year of the Tigers (3rd edn).

B Company 5RAR advancing on Duc Trung with tanks on 7 June 1969. Photograph: The Year of the Tigers (3rd edn).

B Company and the Intelligence Section soldiers from 5RAR inspecting some of the captured weapons including the 75mm RCL seized from the enemy Recoilless Rifle Platoon on 7 June. Photograph: The Year of the Tigers (3rd edn).

At 1300 hours about 100 enemy overran a Popular Force platoon in Duc Trung killing four and wounding seven. Lieutenant Colonel Khan arranged for artillery to bombard the enemy on the northern fringe of the houses and ordered B Company with a troop of tanks to the location. A helicopter light fire team also engaged the enemy. After B Company had swept through the southern part of the hamlet with a troop of tanks, the District Chief, Major Ngo, (with Khan) was informed of many civilians remaining in the danger area. B Company’s advance was halted and the task handed over to local RF troops. As that happened, the enemy withdrew to the north-west under further fire from gunship helicopters and artillery, leaving behind six more NVA dead.19

At 1500 hours Khan ordered D Company to sweep the eastern end of Binh Ba again. This was completed at 1715 hours without major incident. Total enemy casualties for the two days of combat were at least 99 killed in action (KIA) confirmed by body count, eight PWs, one Hoi Chanh (surrendered) and many wounded. Modern Vietnamese histories record however, 53 deaths from 33rd NVA Regiment, plus an uncertain number from D440 Battalion, 12 from C195 Company, about seven from the Binh Ba Guerrilla Unit, one from the Chau Duc District Committee and one from the Proselytising Section. More enemy were reported to have been found later by residents in the tunnels and rubble beneath the houses, making the unconfirmed total 126 enemy KIA but that figure may be inaccurate. Friendly force casualties were one Australian and four South Vietnamese KIA and nine Australian and seven South Vietnamese wounded. The tanks and APCs undoubtedly saved the infantry from more casualties but the Centurions themselves sustained considerable damage.

This battle was the fiercest urban warfare experienced by Australian troops in South Vietnam which the Armoured Corps history later rated as ‘armour’s greatest day in Vietnam.’ The 5RAR after action report also acknowledged that the tanks were a ‘battle winning factor’. Major Blake later wrote to the tank commander for phase 1 on 6 June, 2nd Lieutenant Brian Sullivan, ‘…thank God for you and your tanks.’ It was however, a combined all-arms victory.

The Hoa Long Clash

On 7 June, while fighting continued at Binh Ba, a report came from Hoa Long village, three kms south of Nui Dat, that its north-western hamlet of Ap Bac had been occupied by 200 Viet Cong. The new 1ATF Ready Reaction Company, C Company 5RAR under Major Claude Ducker, was immediately deployed with a composite troop of tanks and APCs. The enemy was occupying what turned out to be 29 well-concealed weapon pits. At 1630 hours, C Company assaulted from the east with the three tanks leading followed by infantry dismounted from the APCs, the last providing rear and flank protection. See Map 4 at right (Map: The Year of the Tigers, 3rd edn). Heavy enemy fire was received from the northern flank and snipers concealed in trees harassed the advancing troops, particularly focusing their fire on the headquarters area. The tanks suppressed the main enemy opposition and the APCs helped silence the snipers but many civilians remained in the hamlet, causing fire control problems for the Australians. The tracks were also particularly useful in demolishing claymores and enemy-occupied houses and bunkers.

When the assault force reached a bund at the western side of the hamlet it moved north for 100 metres, then swept back towards the east to catch that enemy from their rear. Six VC were captured. After two hours of fighting the enemy withdrew and when darkness fell the Australians adopted all round defence near the enemy weapon pits within the hamlet, waiting for VC attempts to retrieve their dead and wounded. There was little activity however and the following day a search revealed six enemy KIA. Two prisoners were taken and later four more were captured in a tunnel by RF soldiers. It was estimated that the VC strength had been closer to 50 or 60, identified as C41 Chau Duc District Company. There were no Australian casualties.

Discussion

The hard fought, vicious battles at Binh Ba and Hoa Long, known respectively as Operations Hammer and Tong, were conspicuous victories for the Australians whose efforts thwarted the enemy attempts to display an ability to freely strike civilian targets close to the Task Force base in Phuoc Tuy. Subsequently, a battle honour for the Binh Ba action was awarded to the Royal Australian Regiment, the 1st Armoured Regiment and the 3rd Cavalry Regiment. The Battle of Binh Ba was also 33rd NVA Regiment’s major confrontation with the Australians in the war.

The HQ 1ATF Vietnam Digest for the period 1-6 June 1969 assessed the strength of 33rd NVA Regiment to have been 1,075 troops. D440 Battalion was additional to that. Accordingly, during the first phase of the Ready Reaction force assaulting Binh Ba on 6 June, the Australian sub-units with 109 soldiers, were vastly outnumbered. This figure is derived from 65 men in the under-strength D Company plus its artillery forward observer party of two, 13 APCs with crews of two (26) and four tanks with crews of four (16). The 1ATF numbers increased as the day progressed however, but were still considerably fewer than the enemy force. In view of the Australians being greatly outnumbered, it was their tactics and formations plus their firepower, particularly from the tanks and APCs, as well as artillery and helicopter gunships, that gave them the edge. Further, the Australian casualty rate was kept low by the enemy focussing their RPG armour-piercing fire primarily at the tanks. Had they aimed more at the infantry-laden APCs during the first assault, greater casualties would have undoubtedly been sustained. Moreover, the NVA plan of striking Binh Ba and drawing out the Australians to then be ambushed was an abject failure. Only two incidents occurred that could be vaguely construed as attempted ambushes. The first was the initial RPG firing at the two sole tanks on Route 2 in the early morning of 6 June. The second was when the ATF Ready Reaction force was actually moving to the rescue of Binh Ba and there was some insignificant small arms fire at it from west of Route 2 near Duc My, fire that was swiftly silenced by the tanks. If these were really from the set enemy ambushes, it is surprising they were silenced so readily and easily. Several Communist Vietnamese historical accounts relate however, that the planned ambush was intentionally not sprung. 20 The 33rd Regiment and D440 Battalion versions were similar, that the Australian relief force was ‘spread out in groups of two-and-three vehicles and did not fall into the Regiment’s ambush – so the Regiment’s tactical headquarters decided not to attack’. In other words, the Australian force was moving in such a sound tactical formation that ambushing them would not have been successful. On the other hand, the Chau Duc History in 2004 said that ‘The Australians did not enter our ambush as planned’. Major Blake’s opinion was that any ambush along Route 2 from Nui Dat to Binh Ba was highly unlikely because the ground was flat, both sides of the road had been ‘landcleared’ and there were no defile or natural obstacles to slow or channel a mobile force.21 Lieutenant Colonel Khan believed later that the RPG fired at the two lone tanks was possibly due to poor fire discipline by a ‘wayward soldier’ who may well have later been severely punished.22 On the other hand the 33rd NVA history quoted above said that, ‘Comrade Bảy [the battalion 2ic of its 1st Battalion] ordered that the enemy had to be attacked and not allowed to advance’. If this was the response to his order, it was a very poor attempt to block the Australian advance, so Khan may well be correct about later repercussions. It is also likely that the enemy contacted by B Company at 0645 hours on 7 June was not only the Recoilless Rifle Platoon but also a company of D440 Battalion. 23 But what of the other two 33rd NVA battalions? It is likely from the somewhat contradictory and inconclusive 33rd Regimental history that its 3rd Battalion was initially in a support and ambush position near Route 2 to the north of Binh Ba while its 2nd Battalion was similarly assigned further south. As the battle progressed, ‘neither the 8th [2nd] Battalion nor the 9th [3rd] Battalion were able to deploy’ which probably meant that the enveloping manoeuvres of the Australian force around Binh Ba prevented these two reserve NVA battalions from responding, with the possible exception that it may have been one of these units that attacked Duc Trung on 7 June. Whatever the fact, their failure to deploy and counter attack into Binh Ba and in particular, the failure to ambush the Australians, a major objective of the whole enemy operation, would no doubt have led to reprimands from higher headquarters. Another question to have arisen subsequently is whether or not the Australian Task Force Commander should have briefed the Ready Reaction force of 33rd NVA Regiment’s presence in the Province (see Maps 1 and 2 above). The history of 547 Signal Troop (at page 375) refers to Brigadier Pearson being informed of 33rd Regiment movement ‘towards the general area of Nui Dat’. The source for that statement is given as ‘various writings by Adrian Bishop’ a cryptanalysts-linguist Corporal with the unit, but unfortunately, his recollections cannot be assessed by this writer as to either their contemporaneity or their accuracy. Indeed, according to Bishop’s correspondence to Chamberlain in March 2012, what he really said was, …on 3 June … we were able to brief the Task Force Commander and the GSO2 Intelligence that HQ 33rd NVA Regiment had crossed the Sông Ray (River) and was located to the north of 1ATF. This of course is a rather different description of movement ‘towards the general area of Nui Dat’ particularly when the distance of how far north is considered. In fact, Maps 1 and 2 clearly show the physical evidence of 547’s own tracking of 33rd Regiment to have been about 23 kms north-east of Nui Dat when it crossed the Song Rai and a day later was well north of Binh Ba and at least 16 kms from Nui Dat. Indeed, it was then located squarely within the AO of 6RAR/NZ. With respect to such inconsistencies, it should be noted that the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal inquiry said that ‘there are discrepancies in recorded histories about 547 Signal Troop operations prior to the Battle of Binh Ba.’ 24 Was this intelligence briefed to Lieutenant Colonel Butler? Brigadier Pearson is reported to have said about the use of 547 Signal Troop revelations: 25 Although there was a strong restriction as to the use of the information given to us by 547 Troop, we managed to advise our operational troops of the location, impeding moves and so on, of the enemy. This allowed our combat troops to carry out operations successfully, particularly night ambushes. The 6th Battalion’s log shows that Brigadier Pearson visited Butler at FSPB Virginia on 4 June so there would have to be a strong presumption that he informed him of the 33rd Regiment’s movements. Accordingly, such information was undoubtedly foremost in Butler’s mind when, early next morning at 0435 hours, his unit experienced radio jamming of his radio nets near FSPB Virginia. 26 But what of the briefing for the Ready Reaction force heading towards Binh Ba? Despite the 1ATF commander having knowledge of 33rd Regiment’s presence in the province just kilometres north-west of Binh Ba and within the AO of 6th Battalion, the information he received when Binh Ba was actually attacked was that the interlopers comprised two platoons of VC, with no mention of NVA regulars. That being the case, it could be argued that it was only remotely relevant to the Ready Reaction force briefing. On the other hand, a warning of NVA Main Force troops being within striking distance would have alerted Blake’s force of potential conflict with them. Also, being aware of the oftenused enemy tactic of luring rescue forces into an ambush, Blake and De Vere may well have considered an alternative (hooking) approach when deploying towards Binh Ba. In hindsight, despite the secrecy surrounding SIGINT revelations, Khan, Blake and De Vere should have been briefed about the NVA regiment. It is to the great credit of the Australians that they overcame the ferocity of their opposition as their rescue of Binh Ba progressed.

Notwithstanding the Communist defeat, within weeks of the battle, the 33rd Regiment’s political cadre published some morale-boosting hyperbole in a News Bulletin extolling their victories in 1969, including a derisive poem27 about the ‘rats’:

The news has spread far and wide,

Some Australian soldiers have left their homes and come here,

Where there are rivers and streams, swamps and marshes,

High mountains, and low hills – all obstacles to them,

They crept and groped everywhere seeking our sanctuaries,

Their soldiers painted their faces and ambushed our tracks.

In the fires, the people’s houses were set aflame,

The fleeing Australians showed their true rats’ tails,and we laughed derisively,

Let’s tell the story from beginning to end,

In Long Đất District everyone knew,

It was just the Australians that had to take the bitter pill,

In this time of death they fled seeking rescue,

This time the Australians met with the ‘VC’,

They felt heavy as if their limbs weighed a thousand kilos,

The ‘Royal’ troops even took off their trousers,

Threw down their guns, cast away their ammunition,and fled afar,

Their deafening screams gave us headaches,

We ask whether the Australians have any capability remaining,

Is it true that they’ve eaten too much candy,

The ghosts of the Australian soldiers fear the mountains and rivers of our land,

The 19th Company (the 33’s Sapper Company) fought very skilfully,

The 5th Company (the 1st Company of VC D440) also joined hands with us very well,

The people of Long Đất are very appreciative,

Blossoms flower on a happy summer afternoon.

The ‘Red Rats’

1ATF vehicle symbol which, to the Vietnamese, was a red rat.

What, however, was this name ‘rats’ (also known as the ‘red rats’) all about? It was derived from the red kangaroo symbol painted on many Australian military vehicles in Vietnam as well as on their road signs and unit signs. The red kangaroo became to the South Vietnamese peasants, the ‘red rat’ and the Uc dai loi Australians, became the Red Rats.

33rd NVA Regiment Memorial.

33rd NVA Regimental Museum.

Battle of Binh Ba Commemorations in Vietnam

Although Binh Ba was not the home base for 33rd NVA Infantry Regiment, there is both a memorial and a regimental museum erected for it in the village. This seems to be a response to its tragic major losses in the Battle of Binh Ba and many of its veterans later settling in the south.

Chamberlain advises that Vietnamese veterans of the 33rd NVA Regiment have held a 50th anniversary memorial service at their complex in Binh Ba village, arranged by their Vung Taubased Liaison Committee. The event was attended by Hoàng Đình Chiến, believed to be the last surviving 33rd Regiment soldier to have fought in the battle.

Earlier, Hoàng Đình Chiến gave a presentation on a ‘tactical map’ of the Battle of Binh Ba, at which he noted that ‘53 of my comrades were killed and buried in a mass grave.’ The Hà Nội Liaison Committee has submitted a proposal to Vietnamese authorities that the Binh Ba memorial be acknowledged with ‘National Status’.

Hoàng Đình Chiến describing his ‘tactical map’ for the Battle of Binh Ba.

Australian commemorations

The latest of several Australian commemorations for the Battle of Binh Ba was held at the Australian Vietnam Forces National Memorial on Anzac Parade, Canberra (at right) on 6 June 2019. It was the 50th anniversary. Australian commander of the force Brigadier Colin Khan (ret’d) spoke of the battle before wreaths were laid by veterans of the engagement and by the family of Private Wayne Edward Teeling who lost his life on that day in 1969. It had been his first operation with the battalion. Later that afternoon, a Last Post Ceremony was held in honour of Private Teeling at the nearby Australian War Memorial.

Sources

1. Ernest P. Chamberlain:

a. Research Note 9/2019, Vietnam War: The Battle of Bình Ba – June 1969: Enemy Aspects, 10 May 2019;

b. The 33rd Regiment, North Vietnamese Army; Their Story (a translation, compilation and commentary of several monographs by Chamberlain in 2014);

c. The 33rd Regiment, North Vietnamese Army; Their History (a translation and commentary by Chamberlain in 2017);

d. The History of the Bà Rịa-Long Khánh 440 Battalion (1967-1979) (a translation and commentary by Chamberlain in 2011);

e. The Viet Cong D440 Battalion: Their Story, (a translation and commentary by Chamberlain in 2013);

f. The Viet Cong D445 Battalion: Their Story – and the Battle of Long Tan (a translation and commentary by Chamberlain in 2016);

g. Monuments and Memorials of the War in Phước Tuy, Long Khánh, and Vũng Tàu, 25 April 2019.

2. A.K. Ekins with I.G. McNeill, Fighting to the Finish, Allen & Unwin, 2012.

3. M.R. Battle and D.S. Wilkins, The Year of the Tigers, revised 3rd edition, Australian Military History Publications, 2009.

4. R. Hartley and B. Hampstead, The Story of 547 Signal Troop in South Vietnam 1966 to 1972, 2nd edition, 2016.

5. D.G. Hay, The Battle of Binh Ba; One take on a very muddied history, Tales from the Treehouse, 2016.

6. M.F. Fairhead, A Duty Done; A summary of operations by the Royal Australian Regiment in the Vietnam War 1965-1972, RAR Association, 2014.

7. B.K. London OAM, DCM, A Platoon Commander’s View, at website: http://www.5rar.asn.au/tours/battle_binhba.htm

8. R. Gallacher, The Battle of Binh Ba (article) at website http://www.5rar.asn.au/narrative/Battle-ofBinh-Ba.pdf.

9. Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal inquiry into recognition for service with 547 Signal Troop in Vietnam from 1966 to 1971 (unsuccessful claim for the Meritorious Unit Citation).

10. Australian War Memorial (AWM) archival ‘Collection’ records.

11. Unit war diaries of HQ 1ATF, 5RAR, 6RAR/NZ, 1Armoured Regiment and 3Cavalry Regiment.

Endnotes:

1 655 RF Company post (strength 106 men) was located just north of the Binh Ba airstrip.

2 Chamberlain, The 33rd Regiment, North Vietnamese Army; Their History, 2017, at p.53, translates the contradictory history that 2nd/33rd Battalion was sited to the north and 3rd/33rd Battalion to the south, but he concludes this to be an error by the Communist history writing team. Chamberlain is of the view that, on balance, 2nd/33rd Battalion was sited in an ambush position to the south of Binh Ba.

3 Fairhead, A Duty Done, p.86.

4 The work and role of 547 Signal Troop were secret and remained so until relatively recent times- Inquiry by Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal, p.37.

5 Some interpretation was possible by ‘traffic analysis’ including by volume and type of signal transmissions (eg, urgency) that might indicate operational status of units and formations. Australian intercept operators could also sometimes identify a specific enemy transmitter’s ‘hand’- his/her Morse keying style. See Chamberlain, The Viet Cong D445 Battalion: Their Story, Annex E, p.293 including f/n 35.

6 Chamberlain, Research Note 9/2019, Vietnam War: The Battle of Bình Ba – June 1969: Enemy Aspects, 10 May 2019, p.16.

7 Op cit, p.16, f/n 59.

8 Chamberlain, The 33rd Regiment, North Vietnamese Army; Their History, pp.52-55.

9 Suối Nghẹ was a resettlement village (in 1967) with a population of 1,040 located about midway between Nui Dat and Binh Ba.

10 It is uncertain if it was the 33rd Regiment or D440 RCL Platoon as both histories refer to ‘our’ RCL that was captured on 7 June. See 33rd Regiment; Their History, p.54 and D440 Battalion: Their Story, p.67.

11 In fact, it was not from Duc Trung but from the direction south-west of Binh Ba. See the Australian account that follows.

12 Chamberlain, The Viet Cong D440 Battalion: Their Story, pp.66-7.

13 While this refers to an attempt to break through from the north, it was to the south-west of Binh Ba that the RCL was captured by B Company 5RAR.

14 5RAR After Action Report for Operation Hammer of 11 June 1969, para 12.

15 HQ 1ATF (G Ops) log 6 June 1969, serial 542 (AWM RCDIG1027954).

16 Gallacher, The Battle of Binh Ba.

17 Hay, The Battle of Binh Ba; One take on a very muddied history, p.42.

18 5RAR log 7 June 1969, serial 58; see also 5RAR After Action Report, op cit, p.2.

19 5RAR After Action Report, op cit, p.3.

20 Chamberlain, Research Note 9/2019, op cit, p.23; 33rd Regiment ‘Their Story’ (2014) p.65.

21 Email from M.P. Blake to the writer of 17 May 2019.

22 Address by Brigadier C.N. Khan DSO, AM (ret’d) at the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Binh Ba in Canberra on 6 June 2019.

23 The Communist unit histories are unclear about the actual locations of 2nd and 3rd Battalions of 33rd NVA Regiment but the writer’s assessment is that it was more than likely to have been D440 Battalion that provided the Company in this situation.

24 Inquiry into recognition for service with 547 Signal Troop in Vietnam from 1966 to 1971, p.77, f/n 62.

25 Inquiry (op cit), p.88.

26 HQ 1ATF (G Ops) log 5 June 1969, serial 422 (AWM RCDIG1027954).

27 Chamberlain, Research Note 9/2019, op cit, p.47.