By Raymond Gallacher*

Part 1

“Big contact tonight in the Binh Ba rubber. Troops hit with RPG’s. Ready Reaction Force went out in APCs.”

Quotation from the Wall of Words at the Australian Vietnam Forces Memorial Canberra.

June 1999, Vietnam.

Greg Dwiar left his wife’s side and stood alone for a moment. The colours of the rubber plantations and the smells and sounds of the village had not changed. He could have been back in jungle greens. Memories flooded back and he stood quietly and let the sounds and images from thirty years before wash over him. The villagers eyed him suspiciously; foreigners did not come here. One approached him warily.

‘ Why are you here?’

‘ I fought here,’ Greg said gently.

‘ You fought here?’ the man said suspiciously. ‘ There was no fighting here.’

‘ There was a battle here, in this village. I fought in those rubber trees.’ He pointed to the plantation south of the village.

In communist Vietnam there is little time for doubt or debate. The villagers told him firmly,‘ There was no battle here. No battle in Binh Ba.’

6 June 1969, Vietnam.

The village of Binh Ba was at peace in the early morning. It was a community of plantation workers and was prosperous by the standards of South Vietnam in 1969. The homes were of brick and the roofs were tiled. Gardens were well tended and trees provided some shade. Only the military presence was out of tune with the scene. Route 2 cut past the eastern side of the village and military traffic was commonplace. In particular Australian and New Zealand military traffic was part of everyday life for the people of Binh Ba, as they had the fortune of being only four kilometres north of the Australian Task Force base at Nui Dat.

A Centurion tank and a recovery vehicle moved slowly north up Route 2 from Nui Dat. The commander of the Centurion had been told that Binh Ba was free of Viet Cong and its political elements and that Regional Forces were in command of the village and the surrounding hamlets. The tank crew had every reason to believe their journey would be without incident.

An RPG round flashed out from cover and hit the Centurion square on its turret. The shot was from close range and the rocket penetrated the hull and rocked the tank on its suspension. The Centurion was a good tank, designed by the British for service against the Soviets in Western Europe. But this RPG 7 crew were either experienced or lucky and the Centurion, call sign 2 Zero Delta, was incapacitated; the radio operator was wounded and the turret would not traverse. With no infantry support available 2 Zero Delta was in a vulnerable position. The armoured recovery vehicle behind it ground forward firing its .30 calibre machine guns into any likely looking spot. It was a big-hearted move for the crew of the poorly armed service vehicle, but fortunately no further RPG rounds came from the village. When the firing of the .30 calibre weapons stopped Binh Ba seemed as quiet as ever. 2 Zero Delta ground further north towards the nearby post at Duc Thanh. It seemed to be the end of a small incident, the kind that happened every day in Phuoc Tuy province. A report was sent to Nui Dat where the incident was considered worth investigating. It was yet another stray shot in a long war but this one would not fade away and Binh Ba would become the scene of an intensive battle for forty-eight hours.

1st Australian Task Force (1 ATF) had arrived in South Vietnam with the simple instruction, ‘Take over Phuoc Tuy’. 1 ATF had put its stamp firmly on their area of operations with a strategy of a strong physical presence in the hills, jungles and villages of the province. Patrolling, ambushing and continual pressure had been put on the 274 and 275 VC Main Force Regiments. There had been large set-piece battles too, not just the encounter at Long Tan but also at the defence of Fire Support and Patrol Bases of Coral and Balmoral in 1968. 274 and 275 Regiments and their local elements had been severely mauled on every occasion. There was now a gradual understanding that North Vietnamese Army units were in the area and may be in some strength. As always in the Vietnam War, intelligence was the most difficult of games.

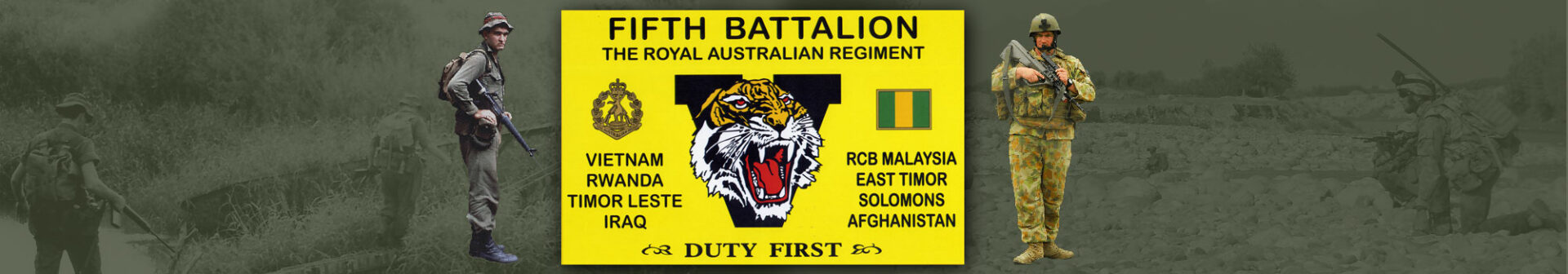

The 5th Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment (5 RAR) was on its second tour of Vietnam and was a tested formation. The soldiers were a mixture of Regulars and National Servicemen – an arrangement which caused friction in other armies but not amongst the Australians. They had been involved in the battle of Long Tan in 1966 and now in June 1969 they were at Nui Dat base again. 5 RAR was resting between operations and glad to be away from large-scale manoeuvres to enjoy whatever amusement life ‘The Dat’ could offer. For individual soldiers it meant days of general housekeeping, maintaining equipment and cleaning kit, or perhaps just listening to the radio; maybe music or ‘Chicken Man’. A Company was enjoying some short Rest and Convalescence leave in the seaside town of Vung Tau where the other companies would also rotate through over the next several days. Brian Bamblett, a section commander in 10 Platoon, D company, remembers it as a day of ‘house keeping, making beds and cleaning equipment.’

10 Platoon commander, 2nd Lieutenant John Russell, remembers, ‘We had been on operations for some time. Some of us were feeling pretty run down and we were looking to get some sun on our backs.’

It was not all housekeeping however. D Company was also the Ready Reaction Company for the Task Force, on 30 minutes notice to move. Small arms were ready, their equipment was ready and their ammunition and rations were already packed.

Major Murray Blake, commanding D Company, 5 RAR, had concerns of his own. Many of D company’s personnel were on promotion courses or training that put them out of use and he was left with light resources if the blue light started to flash. So far however, early on the 6th June the diggers were having a tranquil day.

For the armour, both the tanks of 1st Armoured Regiment and the carriers of 3rd Cavalry Regiment, even a day at Nui Dat was hard work. The vehicles had to be maintained due to the pressure on them from their arduous journeys to support other operations where 6 RAR and 9 RAR were in action. In particular, there was always damage to contend with from that bugbear for all units in Vietnam mines.

Others in Phuoc Tuy province were having anything other than a peaceful morning. 6 RAR was newly arrived in country and was engaged in operations ten kilometres to the north of Nui Dat. What should have been warm-up patrols evolved into heavy fighting. The pressure from 6 RAR’s operations was having a direct effect on the enemy and pushed across the NVA supply lines. What the Australians did not know was that they were also disrupting the movement of an NVA battalion. As resistance increased 6 RAR was in need of support and the Centurions were lending their evervaluable fire support.

The Centurion tanks had not always been considered so indispensable. It had been thought there was no place for them in Vietnam in this war of patrolling and ambush. The tankers had been given the unkind nickname ‘The Koalas’ as they were not to be shot at or sent overseas. But the armour had proved their worth firing canister in defence of FSB Coral, the APCs had been crucial at Long Tan, and the tanks, in particular, were always welcomed by the infantrymen during bunker clearing.

A Centurion tank with a recovery vehicle had been sent to aid 6 RAR but at eight o’ clock had been stopped, literally, in it’s tracks outside Binh Ba.

Binh Ba was well known to the Task Force. This village of plantation and farm workers had a population of about one thousand and would, in normal times, have been quietly prosperous. The prosperity and the proximity to Nui Dat base made the village a target for Viet Cong tax collectors as well as assassination squads. As part of the hearts and minds ethos the Australians had occupied the village in a benevolent way on 5 RAR’s first tour when Binh Ba welcomed a rifle platoon with mortar support. There is even a painting showing gifts being given to the villagers. Perhaps inevitably, the needs of more complex operations meant that Task Force soldiers could not be spared for security duties and the village was handed over to the Regional Forces. Intelligence reports now suggested that two Viet Cong platoons had infiltrated the village and that the RF were no longer in control.

Brian Bamblett was told that D Company were to go and investigate the situation at Binh Ba. ‘Our kit and ammunition were already packed. We knew we were on standby and that anything could happen. I admit I did feel an adrenalin rush. After two years in Vietnam I just thought, ”Here we go again.”’

Bill O’ Mara and Greg Dwiar of B Company were aware of D company’s preparations and did not expect it to amount to much. They were the backup rifle company and they fully expected to have lunch in the relative comfort of the Dat. Bill O’Mara was a keen photographer and made a mental note to keep his camera handy, just in case anything ‘interesting’ happened. For Greg Dwiar, who was a relatively new arrival in Vietnam, he was getting used to the everyday tasks of platoon life and trying to fit in with his new mates. So far, for Greg, it had been nothing except routine. He had only been in 6 Platoon for two days and was still feeling his way around.

D and B companies may have been enjoying a little peace but there was little of any sort of tranquillity in the rest of Phuoc Tuy province. As described above 6 RAR’s fighting had intensified as it pushed over one hornet’s nest after another.

Major Blake considered the intelligence available and it seemed that two Viet Cong platoons had infiltrated the village and that the RF were no longer in control. Presumably it was an RPG crew from these platoons who had fired on the Centurion. Colonel Colin Khan, Major Blake and the other experienced hands of 5 RAR were aware of the unreliability of the sources of intelligence. Intelligence gathering and analysis in Vietnam was a perennial problem. Local Force VC already fed back superb intelligence from observation and infiltration. Their assassination squads, now probably at work in Binh Ba and the surrounding hamlets, would clear up any they thought guilty of collaboration. Large-scale intelligence from aerial observation was generally of little value as the both Main Force and local VC could hide their movement by keeping to thick cover. The cleared areas including the infamous Light Green in the shadow of the Long Hai Hills, were frequently minedby the Viet Cong to inhibit allied movement. Forming up and actual assaults by the Main Force regiments were often under cover of darkness. Both the intelligence war and ground war were like a chase in a dark labyrinth. Surprise was never far away.

Nevertheless, the philosophy of the war was not the immediate problem for Murray Blake or the men of D Company. They gathered weapons, shrugged on their webbing and headed towards the APC troop. The ready reaction force would consist of not just the infantry but also the M113 carriers and a troop of Centurions. The column moved up Route 2 to Binh Ba with as much speed as the tracks would allow. They arrived and formed up south of the village at 10.30 hours.

The shooting had already started. The Regional Force troops were already engaged in fighting but their reports were confused. The reports of the contacts did seem to belie an estimated infiltration force of two platoons. Around the village the rubber trees had been cleared and at times as much as 800 metres were exposed. When D Company and their carriers pulled up in the cleared area south of the village, they soon discovered that some enterprising enemy found them to be within range.

But the opening moves were those of social upheaval so typical of the war. John Russell saw ‘A great stream of people coming down the road: men, women and children. ’The RF were evacuating the village. The diggers could only wait and watch helplessly. The more experienced hands also saw that the evacuation was an obvious escape route for Main Force and Local Force VC. The most frustrating aspect for Allied soldiers all through the conflict was the habit of enemy fighters changing into civilian clothes and mingling with civilians in order to escape final capture. This was a deliberate tactic that ensured that the ATF had to tread carefully among the news cameras as much as amongst the mines.

For Murray Blake, local politics was an immediate problem. He was still in conference with the Vietnamese District Chief. He remembers this still as the main cause of any delay in bringing his force to act on the enemy in Binh Ba. But the village would be ruined by the 20-pounder guns of the Centurions and the inevitable infantry assault. Damage to property would be substantial if the Australians met resistance. It would obviously be a propaganda victory for the Viet Cong no matter what. The ATF Ready Reaction Force began forming up east of the village but still in the area of the cleared rubber trees. Soon the Australians began taking RPG fire.

Meanwhile the RF had consolidated a position well north of Binh Ba. We can only speculate as to the preparations of the enemy within the village at this time.

In the cleared ground the diggers were aware of their vulnerability. Brian Bamblett and his riflemen arrived on their APCs before dismounting when he saw ‘figures running at the edge of the village. I could see no pith helmets or floppy hats, no red stars. I couldn’t tell whether they were VC or NVA. They were just running figures. Then I saw a smoke trail from an RPG. The APCs used bursts of .50 calibre to chase them off.’ An experienced man, Brian looked for cover while D Company got itself organised.

At 11.20 Major Blake was told by the District Chief, ‘Do what you have to do.’

A solution had been quickly thought out: D Company with support of tanks and carriers would form up with Route 2 as the start line and assault from east to west. The combined force would roll through the village streets and clear the enemy. The Reaction Force advanced towards the village; four tanks under the command of 2nd Lieutenant Brian Sullivan led the way while Captain Raymond De Vere’s APCs ferried D Company behind.

At 300 metres the RPGs were within their effective range. The commanders of the Centurions were already firing at houses where they suspected the rounds were coming from. The enemy were trying to effect flanking moves. Although his view was limited, Brian Bamblett was aware of firing coming from the south. Firing was indeed coming from this direction and the tankers were firing canister in return. The operation was heating up.

As always the soldiers of the ATF were not without friends. 9 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force were on call to support the assault. The light fire team of two Bushrangers (an Iroquois fitted with mini-guns and rockets) were to soften up the defending enemy and to prevent their escape from their village. They would follow the simple method of sweeping in the direction of the Australian assault. As always the plan would change as events unfolded. The Bushrangers would expend their ordnance many times over in the hours to come.

Binh Ba was not large, just 200 metres north to south and about 500 metres west to east. It had grid system of four roads running through it. The initial plan was simple. Tanks, APCs and infantry would advance to each block of houses. The infantry would clear the houses with support from the Centurions and the carriers. A mopping-up force was to bring up the rear. The Bushrangers would attack the retreating enemy.

As the Australians pushed through the village, resistance was stiff. Tank commander Brian Sullivan discovered that the well built houses could absorb a lot of firepower and were providing good cover. He found that firing a 20-pounder high explosive round through the wooden doors, or if possible the wooden window shutters, would kill everyone inside without causing too much destruction and leaving rubble behind. Despite superb support from the tanks and the suppressing fire from the carriers of 3rd Cavalry both men and vehicles were coming under increasing amounts of small arms fire and more dangerously for the vehicles, RPGs.

Nick Weir, commanding one of the APCs remembers, ‘We received quite a shock when we came under sustained heavy fire from the first houses as we entered the village.’ Nick’s other abiding memory was the sight of the French plantation owner, ‘He was swearing and spitting at us. All he was worried about was his rubber business.’

The assaulting troops found themselves vulnerable to a determined enemy, well concealed in the built up area. RPG crews roamed the village and the destruction of houses and the physical furniture of the community merely provided them with more cover. The level of firing did not even seem typical of the VC but was the beginning of an indication that there was an NVA presence. Each small group of D Company pushed forward and contact after contact was made. The APCs and tanks expended thousand of .50 calibre and .30 calibre rounds at every suspect doorway or point of fire. The Centurion’s heavy guns were turned on any hardened position. For Murray Blake, ‘The enemy were everywhere, it was like you see in the movies. I even saw blokes dragging a 12.7 mm machine gun up. The other problem was that there were still a lot of civilians around. I saw my men stop firing and run to move frightened civilians out of the way.’ He still remembers this very vividly.

John Russell felt it was, ‘Chaotic. There was an awful lot of firing from the armour. I was aware that we were getting low on ammunition, especially grenades.’

At the end of an hour three tanks were disabled due to damage and crew casualties and Binh Ba had still not been taken. Memories are confused and each man holds only fragments of the battle in his mind. One Centurion was temporarily abandoned while the kit slung on top of it burned. D company and the armour pulled out to the south and then around to the western side of the village.

Murray Blake saw it mainly as a problem of supply. In particular the Centurions needed ammunition resupply and there were lots of casualties from small arms and splinters. In the APCs Nick Weir was, ‘Surprised by the violence of the action.’

For Brian Bamblett, he felt he had been, ‘ Kicked out of Binh Ba!’

Nevertheless the priorities were now ammunition resupply and reinforcement. There was no question of not going back into the village. Murray Blake recalls, ‘We had to. We just had to go back in.’

End of Part 1

Part 2

The situation at Binh Ba required reinforcements. Back at Nui Dat news was coming in that there was a big contact at the village. B Company 5 RAR had been put on standby. They were now given orders to move.

Greg Dwiar, a national serviceman had only been in Vietnam since the 14th of May so to him a digger’s life in Phuoc Tuy province was still an unknown quantity. He was sent as a reinforcement to B Company and immediately settled in finding himself happy in his new surrounding and comfortable with his new platoon mates. He had been in B Company two days and at about 14.00 hours he and the rest were given orders to collect their kit and assemble. The carriers were coming down to their lines to collect them.

In Vietnam there was no slow approach to the face of battle. Modern transport moved a man within the hour. For B Company then, they began their day listening to Hendrix and the Beatles on the American Forces Network and by lunch were climbing aboard a carrier and heading towards the shooting.

Informed only by the occasional episode of Combat or by Vic Morrow, Greg wasn’t too sure what to expect. Greg thought, ‘ I was very apprehensive and a little excited. I thought, “This is what we’re here for so we might as well just go!”’

Bill O’Mara, also of 6 Platoon, did not get too stirred by the thought of moving up in support. He expected the whole affair to be a ‘walk in the park’ but he still took his camera. Like the rest of the riflemen he stowed his kit inside the carriers and then clambered on top to enjoy the view. Moving from Nui Dat to Binh Ba took no more than 20 minutes.

The soldiers of B Company were to ensure that no enemy forces were to leave or enter the village. They deployed in the outskirts of the village in the rubber.

As the column neared Binh Ba, Bill remembers, ‘As we got closer, I saw that the houses were on fire and there were gunships buzzing back and forth.’ It struck him that it might not be quite a walk in the park after all. He did take time to snap a picture from the back of the APC. In the picture, grey smoke is rising from the village and the smudge of the Bushranger can be seen overhead.

B Company pulled up and spread out 300 meters south of the village. Using route 2 as the border of their right flank the company and it’s carriers spread out over some 400 meters in their first blocking position. Their left flank looked on the edge of the rubber plantation. The area was mostly flat and had no obstacles apart from the occasional tree stump. It gave a perfect view. Some men stood up on top to get a better look at the contest in front of them.

Greg Dwiar looked on the spectacle with some interest and a little concern. Apart from the smoke and small arms fire the most obvious sights and sounds were from the Bushrangers. The noise of the mini-guns on the gunships could clearly be heard. They made a high-pitched ripping noise as they spat out cannon shells on enemy positions. Greg wasn’t sure if this was a typical day in Vietnam or not. He thought, ‘If this is what it’s going to be like, I wish I’d never come.’

D Company was now formed up to the west of Binh Ba. They would assault again. This time the infantry, carriers and tanks would move from west to east. A fresh troop of tanks moved up into position and the APCs would give close support. The infantry would lead off at 1400 hours. They would clear the houses supported by X Troop, 1st Armoured Regiment. But with the enemy now in a dense defensive position created by the damage of the first assault it would be a bitter time. One of the problems was that the villagers had bunkers built under or near their homes. Sadly this was a response to living and working in a war zone. Every point of concealment would have to be searched and pacified. It would be nerve-racking work that only the infantry soldier could do. There was no evidence that the hit-and-run guerrillas had evacuated the village. Binh Ba was to turn from a mechanised battle to one of hand-to-hand fighting.

Each infantry platoon had one tank and two carriers in close support. The platoons were broken up into house clearing teams each of three men. The infantry would lead the assault and the tanks and the APCs would follow, with the APCs at the rear spread across the full width to each flank. Tanks would be called up whenever they were needed. This sensible arrangement would suffer from the first contact with the enemy and the confusion of losing control by line of sight. Control of the house clearing teams and control of the supporting vehicles would now be a problem. Although small, it was still a built up environment where observation was restricted and confusion arises quickly. The teams were to clear one row of houses at a time. If all went to plan they would step through Binh Ba one fire team and one house at a time.

D Company moved forward again, they were mounted in carriers at first because the first open space was when they were at their most vulnerable.

Closing with the houses the infantry dismounted and contact was immediate. John Russell looked along the extended line of infantry. At the time he thought ‘There aren’t that many of us and we’re taking fire already.’

Brian Bamblett was aware of the amount of firing in all directions. Private Wayne Teeling was shot dead as his platoon reached the first line of houses. Sergeant Brian London of 10 Platoon ran to the rear of the closest Centurion and picked up the telephone on the chassis. He had been warned that they never worked. Typically it wasn’t working. He climbed up and shouted down the hatch. Brian asked for one round of high explosive into the first building. Brian Bamblett nearby remembers it as canister. The house rocked under the blast and the diggers ran forward and assaulted. Six NVA dead were found in the ruins. This pattern would be repeated again and again.

John Russell found that, ‘There were already dead and wounded in the houses. One man, an NVA soldier came out with his hands up. He was showing me his wound. I sent him back to be taken prisoner.’

The fighting was fierce and confused. Communications and control were lost frequently. The Australians pushed forward with or without direct orders. Sometimes junior ranks would lead and often a private soldier with no more than a few months experience would lead. More experienced men were not around but someone always came forward. Another corner and another room would be taken. The battle was a minute-by-minute venture by private soldiers and NCOs. For Brian Bamblett, ’It was split-second choices and close in fighting inside houses and inside rooms.’

By now, it was obvious that the fighting was far above what could be expected from two platoons of VC. A United States Air force forward controller, call sign Jade Five, offered to help but Ray de Vere was confidant enough that the Australians could manage with their own resources. De Vere directed rocket and mini-gun fire onto targets that would not be pacified and that were causing the advancing diggers to falter.

John Russell and the men of his platoon had now reached the centre of the village. As they approached a town hall like building John saw that there were wires running out of it. He had the presence of mind to cut them. Going inside, he said, ‘We were fired on. I got stuck in the house and I dived behind a low dividing wall. The NVA threw a grenade after me. It went off and I was wounded but still conscious. The NVA put their heads around to see if I was dead.’ John Russell opened fire. Unlike his enemies, he walked away and continued the fight until he was sent back because of his wounds. He shared an APC with the deceased Wayne Teeling on the way back to Nui Dat.

By last light the firing had lessened and the last of the houses were being cleared. As most of the buildings in Binh Ba were now hardly recognizable, the fight had gone underground. The diggers pulled open the coverings of air raid shelters built close to or within each of the houses. Many of the enemy wanted out, they were deafened and shaken by the day of non-stop concussion. They added to the physical and moral confusion by changing into civilian clothing in order to escape.

The assaulting company was equally wrung out. As darkness fell, they were exhausted. But if anyone could sleep they would have to sleep through the artillery. Harassing fire was arranged and the 105th Field Battery was given a huge list of targets. They were to prevent the orderly retreat of the NVA and more importantly to prevent them from forming up again.

As for the night, apart from the crump of artillery on its harassing tasks, the diggers spent the night peacefully. One described it as, ’Deliciously cool’. Some men rested, if they could.

The men of B Company and their carriers formed an all-round defensive position, a circular laager with APCs and riflemen facing outwards. The platoons were to form a blocking position from the corner of the rubber plantations south of the village. Route 2 would be on their right flank. Fatigue took its toll. Bill O’Mara broke all the rules of the night harbour as he sheltered under his tent: he took his boots off to allow a better sleep.

Through the night B Company had a quiet time and saw little activity in front of their blocking position. They waited, spread out just in front of the APCs. Greg Dwiar remembers being ‘Buggered – absolutely exhausted. I wasn’t on first picket so I got a couple of hours sleep. About two in the morning there was a brief contact nearby. Some shots were exchanged but it was pitch black, you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face.’

There had been a burst of firing at 0230 when 4 Platoon opened fire on the enemy in front of them. The inky darkness made the exchange inconclusive although disturbing for Greg Dwiar. He drowsed fitfully for the rest of the night. He was almost relieved when he was to go on picket on the M60 between four and six in the morning.

Greg spent the rest of the night occasionally catching fifteen minutes of closing his eyes until the morning. He was the number two on the M60 and he was to get an alarm call. Don Campbell, the number one on the M60, shook him into full wakefulness, ‘Listen to that!’

Greg became aware of Vietnamese voices. He estimated that they were about twenty metres away.

It was now 6 a.m. on the morning of the 7th, and a large group of NVA soldiers was moving toward them. In a bizarre exchange, and perhaps because of the Australian’s floppy hats and jungle green attire, the two sides waved at each other. Regional Forces were still in the area and B Company thought the column were friendlies. It was their style of arms that then gave them away.

Bill O’Mara remembers being kicked awake in the dawn. ‘I was armed with an M16; I know I fired at least two magazines. I didn’t get time to lace my boots up either.’ A brisk action ensued and Bill fired into the NVA with his boots still loose. The NVA returned fire but panicking soldiers fire high and fortunately for Bill one piece of ordnance detonated well above him. ‘I remember smoke and a green flash. It was an RPG round and luckily it was high in the rubber trees above me.’ Bill, unscathed, fought on.

For Greg Dwiar, this very personal little battle was spent with his head a foot from the roar of the M60. Don Campbell opened up with a massive stream of M60 fire. In his first contact Greg was deafened by the noise and focused on his duties feeding the belts of ammunition. Greg reached out for his SLR; he felt he would be needing it before too long.

The woods lit up with a carnival of tracer, red Australian tracer going towards the NVA and green tracer coming back. Australian heads ducked when the smoke trail of an RPG streaked towards them. Greg was conscious of firing his SLR into the enemy. Later that morning clearing patrols were sent out to confirm NVA casualties. During a quiet moment, Greg Dwiar decided he would reload the 7.62mm rounds into his magazines. He puzzled over why he seemed to have so much ammunition. He was sure he must be down to his last magazine. After careful and discreet counting well away from the eyes of his fellow diggers Greg concluded that he hadn’t fired a shot. His safety catch had been on all through the contact.

For the diggers, endgame was in sight. Elements of both armour and infantry would make a final sweep. The awful final tasks of clearance had also to be done; bringing out the dead and searching for booby traps, searching corpses for vital documents. There would be wounded who must be approached cautiously. Abandoned weapons and ammunition must be collected, as it would give a clue to the always-difficult business of estimating enemy casualties. There may be some combatants who would try to surrender. Intelligence gatherers in particular were always pressing for prisoners, wounded or not. And of course some local Vietnamese, as always, would be caught in the maelstrom. The intelligence gathered quickly proved what the diggers had already guessed; that the village had been occupied by NVA regulars. Bill O’Mara, going into the devastated village saw a camera crew, ‘I was just amazed; they were trying to get some of the diggers to reenact the battle so they could film it. The diggers made their feelings clear as they bypassed the cameramen.’

The Battle of Binh Ba finished at 8:00 a.m. on June 8th after a final sweep. At 9:00 a.m. Australian civil affairs staff arrived to assist in the resettlement of the villagers. We may imagine that their task would have been difficult. The troops returned to base. Despite the intensity of the battle only one man was killed in action: Private Wayne Teeling. It says much for the Australian army medical casevac system that if the dustoff came for you, your chances were high. On the Australian war memorial there are inscriptions of common phrases of the time. One sums up the feelings of the wounded,’ If you got to the landing pad at Vung Tau, you knew you were going to be all right.’

126 confirmed North Vietnamese Army and VC were killed. 1st Battalion 33 Regiment NVA was certainly mauled in the action at Binh Ba. There is no doubt that they made a firm stand at the village and were determined to destroy large assets of the Australian Task Force. They were armed to do so judging by the amount of RPG fire. It is also seems certain that the operation of the Australians further north was putting pressure on their movement. Captured documents later showed that 33 Regiment were trying to get across Phuoc Tuy province in order to get to areas of sanctuary in the northeast.

Finally, what was Binh Ba? Was it a deliberate stand by the NVA? Certainly the first shot on the morning of the 6th was not much of an ambush. Perhaps it was a nervous trigger finger by a young NVA soldier. Did they not expect retaliation by the Australians, or was it a deliberate ploy to entice a part of the Task Force out to fight on ground which they had not chosen? There had been classic encounter battles before but few where the NVA had been so prepared to take on armour. The final decision on Binh Ba must at this point remain with the reader. Debate can continue, as we do not know the intentions of 33 NVA Regiment that day. What is true is that 5 RAR engaged relentlessly with a level of combined arms skill that is to be admired and respected.

Acknowledgements:

5 RAR Association Mr Murray Blake, D Company (Major, later Maj Gen)

Mr David Wilkins, BHQ (Captain, later Col)

Mr John Russell (2nd Lieutenant)

Mr Brian Bamblett, D Company (Cpl, later WO2)

Mr Bill O’Mara, B Company (Rifleman)

Mr David Weir, 3rd Cavalry (Cpl)

The Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

* The author of this article, Raymond Gallacher, is a writer and lecturer from Glasgow, Scotland who has contributed to both magazines and BBC radio. His interest in Australian history arose from having many of his family domiciled in Australia.

Editorial Note: This account does not include detail of the Australian assault on the enemy-occupied hamlet, Duc Trung, just 500 metres north of Binh Ba on 7 June 1969. This initially involved B Company 5 RAR with tanks and APCs, before the South Vietnamese Regional Force Company took over because of large number of civilians still within the village. This action is considered part of the Battle of Binh Ba, from 6 to 8 June 1969.